SECTION CONTENT

SAN JUAN ISLANDS

SAN JUAN ISLANDS

by Barbara Jensen

revised by Barbara Jensen

The marine waters surrounding the San Juan Islands are the richest in the Puget Basin, abounding with plankton, the primary producers in the food chain. The many large bays, wide channels with fast-moving currents, and quiet harbors are prime locations to observe seabirds in winter and migration, Killer Whales, and Bald Eagles—whether by boat or from shore. On land, habitat variety is extensive, with forest, prairies, wetlands, rocky shoreline, and sheltered coves all in close proximity. Lying in the lee of the Olympic Mountains, the islands receive around 25 inches of rainfall a year, compared to 35–40 inches along the mainland to the east. The drier conditions exclude certain plant species common in the damp forests and valleys of Western Washington (for example, Vine Maple, Devil’s Club, Deer Fern, Evergreen Huckleberry) while favoring other, more drought-resistant species such as Douglas Maple, Garry Oak, and Lodgepole Pine. House Wrens—more usually associated with the dry, open woodlands of Eastern Washington—breed abundantly. During migration, Lewis’s Woodpeckers, Mountain Bluebirds, Townsend’s Solitaires, and other species island-hop to and from Vancouver Island and the mainland.

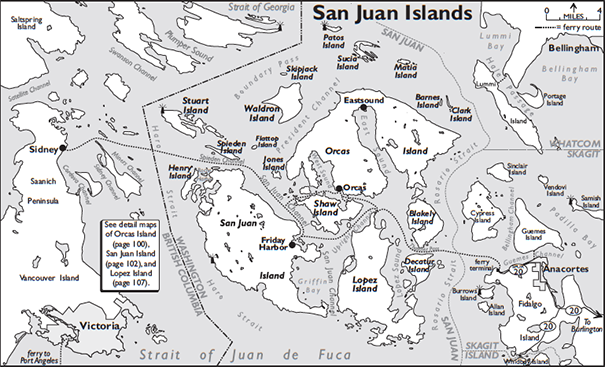

The following accounts describe ferry birding possibilities as well as representative sites on Orcas, Lopez, and San Juan Islands. Allow a full day to bird each. If you have time for only one island, choose San Juan. Even without the small population of Sky Larks, which now appears to be extirpated, this is a major all-round birding destination with the most diverse array of upland and saltwater habitats in the archipelago. Island road systems are confusing at best, and it is helpful to stop by one of the many real estate offices for a free map.

Four of the islands are served by ferry from Anacortes. Some boats continue to Sidney, British Columbia, north of Victoria, and Sky Lark country. Contact Washington State Ferries (WSF) for schedules, fares, and information about travel to Canada. Spaces fill quickly and long waits for the next boat are common at certain days and times. Check the schedules carefully and arrive at the Anacortes terminal at least one hour or more before the scheduled departure time. WSF has proposed to begin taking vehicle reservations in 2015 for U.S. routes. If reservations are available, it is recommended you make one. Contact WSF at 800-843-3779 toll-free statewide, or on-line (the best) at http://www.wsdot.wa.gov/ferries.

From I-5 in Burlington, follow SR-20, then SR-20 Spur west through Anacortes to the ferry terminal; the route is clearly signed. Birding right around the terminal (previous page) will make the wait seem shorter.

SAN JUAN ISLANDS FERRY

Birding from the ferry is best in fall through spring. Most common marine species can be seen on this trip, though some are scarcer or absent in summer. Expected are Surf and White-winged Scoters, Long-tailed Duck, Red-breasted Merganser, Pacific and Common Loons, Horned, Red-necked, and Western Grebes, Brandt’s, Double-crested, and Pelagic Cormorants, Common Murre, Pigeon Guillemot, Marbled and Ancient Murrelets (fairly common to common November–February), Rhinoceros Auklet (common March–September, common to uncommon fall–winter), and Mew and Glaucous-winged Gulls. Many other species occur in smaller numbers or less predictably, among them Red-throated and Yellow-billed Loons. Notable rarities recorded in these waters include King Eider (February and October), Thick-billed Murre (December), Kittlitz’s Murrelet (January), Horned Puffin (July), and Black-headed Gull (September).

The ferry heads westward across broad Rosario Strait. Search here for diving birds, especially alcids. The route then passes among the islands, through narrow channels—sometimes with fast-moving water—and quiet bays. Check calm waters where birds shelter during windy weather. Look along tidal rips or lines on the water for concentrations of feeding birds or “bird balls,” especially cormorants, Red-necked Phalaropes, alcids, and gulls in spring and fall. Steller and California Sea Lions and Harbor Seals fish these areas, too. Bald Eagles and Peregrine Falcons perch in the trees along the shoreline.

ORCAS ISLAND

Horseshoe-shaped Orcas Island is home to Moran State Park—the first state park in Washington—and to the highest point in the islands, Mount Constitution. The shoreline is mostly private, but there are a few public marine viewpoints. The routes take you through some of the best examples of forest, field, and wetland habitats. Woodland birding is good, especially in spring, for typical Puget Lowlands species such as Rufous Hummingbird, Olive-sided and Pacific-slope Flycatchers, Cassin’s, Hutton’s, and Warbling Vireos, Chestnut-backed Chickadee, Red-breasted Nuthatch, Black-throated Gray, Townsend’s, and Wilson’s Warblers, and Western Tanager. Black-capped Chickadee is notably absent, having thus far failed to colonize the San Juans. Trumpeter Swans and many ducks are common in winter. Bald Eagles are numerous all year. The island is overrun with Black-tailed (Mule) Deer, so drive cautiously, especially at night.

From the Orcas Island ferry landing turn right onto Killebrew Lake Road. Check forest and fields along the 2.2-mile drive to Killebrew Lake. Scan the lake for Wood Duck, mergansers, and Pied-billed Grebe. Nearby marshes are home to Virginia Rail, Sora, and MacGillivray’s Warbler. At a junction at the end of the lake, stay left onto Dolphin Bay Road, which soon becomes gravel. Make another inspection in 1.2 miles at Martin Lake, then continue 3.6 miles to a T-intersection where Dolphin Bay Road turns right. Follow it right for 0.6 mile to Orcas Road. Follow Orcas north to Main Street in 2.9 miles and turn right into the town of Eastsound. After passing through town, Main Street becomes Crescent Beach Drive. Stop at Crescent Beach Preserve, just ahead, for waterfowl and for Bonaparte’s, Mew, and Glaucous-winged Gulls or walk the wooded trail. At the stop sign in 1.2 miles, turn right onto Olga Road. The entrance archway to Moran State Park (Discover Pass required) is in 3.1 miles. Drive carefully through this popular park.

In 1.3 miles, turn left toward Mount Constitution. Stop at the Cascade Falls trailhead in 0.3 mile, on the right, and walk to a series of falls along the creek to look for American Dipper. From the Mountain Lake turnoff, on the right in another 0.6 mile, a level, 3.9-mile trail circles the lake (nesting mergansers and forest birds). Continue the winding, steep grade toward the summit. A turnout on a hairpin curve in 1.1 miles, on the left, and another on the right just around the bend, have magnificent views of the surrounding islands. The rocky south-facing slopes are open and grass-covered. Look for Sooty Grouse and Chipping Sparrow along the forest/grass edges. Similar habitat can be explored from two more turnouts 0.6 mile ahead, or from the parking area for Little Summit (elevation 2,040 feet), on the right in a further 0.1 mile. The road ends at the summit parking lot in 1.6 miles. Coniferous forests on the steep, north-facing slopes have Hairy and Pileated Woodpeckers, Golden-crowned Kinglet, Swainson’s and Varied Thrushes, Yellow-rumped Warbler, Purple Finch, and Red Crossbill.

Climb the stone lookout tower, built in the 1930s by the Civilian Conservation Corps, for a 360-degree view of the San Juans, 130 miles south to Mount Rainier, east to the North Cascades, 50 miles north to Vancouver, British Columbia, west to Vancouver Island, and southwest to the Olympic Mountains. Look for Turkey Vultures, raptors, swifts, and Common Ravens. The 2,409-foot summit is at the north end of an exposed, stony plateau with subalpine-like vegetation dominated by Lodgepole Pines (one of the largest forests of this species in Western Washington). Brown Creepers and Townsend’s Warblers may be seen close-up as they forage in the pines. Common Nighthawks nest on bare ground among the scrubby understory of Hairy Manzanita and Salal. Plants such as Rocky Mountain Woodsia, Rosy Pussy-toes, and Dwarf Mountain Daisy that grow here and nowhere else in the islands are outliers of populations in the Olympics and Cascades. To experience this unique habitat (and jaw-dropping views to the east across Rosario Strait and Bellingham Bay), walk the first half-mile of the ridgeline trail that leaves from behind the restrooms. The trail continues to Little Summit (2.2 miles from the parking lot), intersecting another trail that drops steeply down the mountain to Cascade Lake.

By car, return to Olga Road and turn left. The park’s south boundary is in 0.4 mile, marked by an arch on a narrow bridge. Travel 1.5 miles to the intersection with Point Lawrence Road, on the left. Ahead, the road ends in 0.2 mile in the village of Olga, where a public dock provides a vantage point for waterbirds. Go east on Point Lawrence Road, which descends to the shoreline of Buck Bay in 0.2 mile. Gulls bathe in the freshwater outflow of a small creek that enters the bay, and feed on the bay or on the oyster beds and tideflats. Northwestern Crows are common along the shoreline. In migration, a few shorebirds may be present on the beach at high tide. About 0.3 mile after leaving Buck Bay, turn right from Point Lawrence Road onto Obstruction Pass Road, then bear right onto Trailhead Road at a junction in 0.8 mile. This potholed road passes through fine deciduous forest and a freshwater marsh (rails), ending in 0.8 mile at the trailhead parking lot for Obstruction Point Campground (Discover Pass required). A half-mile trail leads first through dense mixed woodlands, then open, dry forest of Douglas-fir and Pacific Madrone on steep slopes, to the campground and beach park. The site hosts a cohort of lowland forest birds including Hutton’s Vireo, Steller’s Jay (in the San Juans, found only on Orcas and Shaw), Chestnut-backed Chickadee, Red-breasted Nuthatch, Brown Creeper, Golden-crowned Kinglet, Dark-eyed Junco, and Black-headed Grosbeak. When the tide is running, Marbled Murrelets and other seabirds feed along the tidal rips where Obstruction Pass meets East Sound, affording good scope views from the beach.

Return to Eastsound and turn left from Main Street onto Orcas Road. In 1.1 miles turn right onto Crow Valley Road and continue 4.1 miles to the village of West Sound and a T-intersection with Deer Harbor Road, turning right. Travel 3.6 miles to Channel Road. Turn right and stop in 0.2 mile by the bridge across the channel between Deer Harbor and the lagoon on the right to check for wintering Common and Barrow’s Goldeneyes, Black Oystercatcher, Black-bellied Plover, Black Turnstone, and Northwestern Crow. On the right in another 0.6 mile is the start of Richardson’s Marsh, one of the most impressive freshwater marshes in the islands. Find a place to pull completely off. Walk the road for the next 500 yards, peeking through and over the bordering vegetation where you can. Though not very productive in winter, the open waters and extensive growth of cattails and other emergent vegetation can be excellent in spring and early summer. Look and listen for Wood Duck, teals, Hooded Merganser, Pied-billed Grebe, raptors, Virginia Rail, Sora, Rufous Hummingbird, Willow Flycatcher, Tree and Violet-green Swallows, Marsh Wren, Common Yellowthroat, and Red-winged Blackbird. Go back to Deer Harbor Road, turn left, and continue through West Sound to Orcas Road (0.8 mile past the junction with Crow Valley Road). Turn right; it is 2.4 miles to the Orcas ferry dock.

Almost as large as Orcas but gentler in relief and less sprawling, San Juan Island offers a more complete set of habitats and excellent birding access. In one day of intense birding (two days is better), you may find a large variety of birds along dry, rocky coastlines with stands of Garry Oak and Pacific Madrone; in mixed forests of Douglas-fir, Bigleaf Maple, and other species that thrive in moister places; in extensive farmlands, open fields, freshwater marshes, and wetlands; in saltwater habitats of protected bays, mudflats, and channels with swift tidal currents; and on windswept grasslands overlooking the Strait of Juan de Fuca where Sky Larks once lived. Killer Whales and other marine mammals are easily seen from shore in the proper seasons. Numerous records of passerine rarities include Brown Thrasher, Red-throated Pipit, Tennessee Warbler, Indigo Bunting, and Lawrence’s Goldfinch. With more consistent coverage, San Juan Island would probably be revealed as a standout songbird vagrant trap. The following itinerary visits a selection of sites in a clockwise loop from, and back to, Friday Harbor.

From the Friday Harbor ferry ramp, turn right onto Front Street, then left onto Spring Street, and continue through town. Spring Street becomes San Juan Valley Road, turning westward across the broad, open San Juan Valley. This is a productive area for raptors, but stopping along the narrow, busy road is dangerous. Park at a pullout on the left at Douglas Road (1.6 miles). Scan or walk carefully along San Juan Valley Road checking for Western Bluebirds in the summer. The wetlands and farmland can host Yellow-headed Blackbirds in summer and swans and ducks in winter. Drive 1.6 miles south along Douglas Road and scope from the corners of Madden Lane (0.7 mile), Little Road (another 0.7 mile), and Bailer Hill Road (0.2 mile farther) to check the fields and wetlands for Golden Eagle and many other species. Backtrack along Douglas and turn right onto Little Road. In 0.4 mile (check fences and oaks for Western Bluebirds), turn right onto Cattle Point Road, which passes through impressive stands of Garry Oak on dry, rocky outcroppings, intermixed with stands of Douglas-fir, open pastures, wetlands full of willows, and Pacific Madrone along the shoreline. Turn left at Jensen Bay Road (1.2 miles) and pull off occasionally to walk or scan these habitats. Olive-sided Flycatchers, Western Wood-Pewees, and Pacific-slope Flycatchers nest in the forests. The edge between pasture and forest can be good for Rufous Hummingbird, House Wren, and Orange-crowned and Black-throated Gray Warblers. The end of the road faces Griffin Bay and San Juan Channel, yielding scope views of ducks, loons, grebes, and alcids.

Return to Cattle Point Road and turn south. It is 1.5 miles to the visitor center entrance at American Camp, one unit of the San Juan Island National Historical Park. Drive in and park to bird woodlands and prairie. Bald Eagles nest within sight of the visitor center, and the nearby forest is good throughout the year for the usual flocks of chickadees, nuthatches, Brown Creepers, and wrens. Conifers here are gnarled from fierce winds that rip and snap off branches and treetops. This is a notable landfall for birds in migration. Possibilities in fall and spring are Lewis’s Woodpecker, Red-breasted Sapsucker, Mountain Bluebird, Townsend’s Solitaire, and MacGillivray’s Warbler. Breeders include Rufous Hummingbird, Hutton’s Vireo, Swainson’s Thrush, Townsend’s Warbler, and Red Crossbill. Water-stressed glacial soils are covered in extensive grasses. American Golden-Plovers, Whimbrels, and Snow Buntings can be here in the fall. Winter birding can be a challenge because of strong winds. Walk eastward to the top of the Redoubt, which overlooks the prairie. Spring flowers are abundant. Great Camas colors the area deep purple April to June. The bulb of this lily was an important food item of Native peoples, who regularly burned extensive areas of the islands to keep the woody plants in check and camas prairies open. Scan toward the water for Northern Harrier, Short-eared Owl, and Northern Shrike. European Rabbits introduced in the middle of the 19th century and farming have caused much disturbance, but the National Park Service is working on a major prairie restoration that will take many years to complete. Check the marked plots for progress.

Drive east on Cattle Point Road for 1.4 miles and turn right on Pickett’s Lane. Park about 100 yards beyond the crest of the hill. A hundred Sky Larks once nested on these prairies. The colony has been eradicated by predation from introduced foxes and feral cats, but there are occasional reports of one. They could be anywhere; the area just west of this spot was once quite good. Listen for their high-pitched, trilled song and buzzy call-note, and watch for their towering courtship flight in the spring. A walk across the prairie may yield some hidden birds, but be mindful of the numerous rabbit holes.

Continue down to South Beach to look for Vesper Sparrows—the uncommon, local, and declining Westside subspecies (affinis)—in nearby dunes on the left. Dunes may be closed in summer (check for signs and fences) as it is habitat to the rare Island Marble Butterfly. The beach is made of smooth, surf-polished stones. The upper beach is piled high with driftwood thrown there during winter storms. The Olympic Mountains dominate the southern horizon 20 miles across the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Native peoples have used this area for 9,500 years as prime fishing grounds. Heat-shattered rocks can be found from the days of smoking salmon on the beaches. Look for Killer Whales fishing for salmon or possibly a filter-feeding Minke Whale. Scope the water from fall to spring for Surf and White-winged Scoters, Long-tailed Ducks, Common Goldeneyes, Red-breasted Merganser, Pacific Loon, Horned and Red-necked Grebes, Common Murre, Pigeon Guillemot, and Marbled Murrelet (usually found in pairs). Summer is a poor time for marine birds except for breeding Pigeon Guillemots and Rhinoceros Auklets. In late summer Cassin’s Auklets can sometimes be seen, and there is even a small possibility of Tufted Puffins. In the fall look for Horned Larks and American Pipits in the dunes by the beach.

Return to Cattle Point Road, turn right, and drive 2.1 miles to the picnic area at Cattle Point (Discover Pass required). This is one of the best places in Washington for wintering seabirds. Turbulence resulting from the high-volume tidal exchanges (at times, 12 vertical feet in one tidal cycle) in the narrow (mile-wide) Cattle Pass keeps sediments suspended throughout the water column. This provides food to the abundant zooplankton, which in turn feeds the small fish upon which the seabirds prey. Harlequin Duck, Pelagic Cormorant, Black Oystercatcher, Black-bellied Plover, Black Turnstone, Surfbird, and Rock Sandpiper (uncommon) can be seen on the rocky shoreline and on Goose Island just offshore. Scope the rafts and single seabirds feeding mid-channel. Steller Sea Lions feed in the area and haul out on Whale Rocks to the southeast, where their golden-colored bodies are fairly easy to find with a scope. Listen for the roar of the 2,200-pound males from September to May. Nearby pocket beaches are places to find migrating sandpipers or birds trying to stay out of the wind. Raptors work the shoreline. Belted Kingfisher and Northern Rough-winged Swallow nest in the sandy cliffs. The rocky headland here is covered with deep glacial striations—a reminder of the massive, mile-thick ice sheet that passed over the islands during the last ice age. Go back along Cattle Point Road and turn left onto False Bay Drive, 1.2 miles past the visitor center entrance. On the right within a few hundred feet, Panorama Marsh is worth a look. Trumpeter Swans winter here, as do Gadwall, Northern Shoveler, Green-winged Teal, Ring-necked Duck, Bufflehead, and Hooded Merganser. Wood Duck and Pied-billed Grebe breed in the wetland, which is also good for breeding songbirds. Continue on through open farmland interspersed with mixed forests of Red Alder, Bigleaf Maple, and Douglas-fir, with views across the strait to the Olympics.

In 2.5 miles, stop at the head of False Bay, a University of Washington biological preserve and one of the few large, muddy bays in the islands. At low tide, when this shallow bay empties out for about a mile, the sulphur smell from algae can be powerful. High tide pushes the birds close to shore—even then, a spotting scope is useful. A freshwater stream from San Juan Valley enters the bay a couple of hundred yards to the west. Large numbers of American Wigeons (check for Eurasian Wigeons) feed here in the winter along with many other ducks. This is the most reliable place on the island for shorebirds in migration (Sharp-tailed Sandpiper has occurred in fall) and for Great Blue Herons and wintering Dunlins. Bald Eagles are numerous, as food is ample and nest sites are plentiful around the bay. Check willows along the shoreline for songbirds.

Continue north on False Bay Drive and turn left in 0.8 mile onto Bailer Hill Road. Long-eared Owl has been found in this lower end of San Juan Valley among the hedges and fields. Ranchos Road to the right in one mile is good for wintering raptors. Bailer Hill Road continues west, then swings north along the coast, becoming Westside Road. Turnouts provide spectacular views across Haro Strait to Vancouver Island and Victoria, British Columbia. The channel can be full of birds or seemingly empty, much depending on the wind direction and tides. From spring to fall, Killer Whales concentrate here to feed on salmon heading back to the Fraser River to spawn. Lime Kiln Point State Park (Discover Pass required), which is 4.8 miles from False Bay Road, and San Juan County Park (another 2.4 miles) are excellent whale watching points. Look also for marine birds and Black Oystercatchers. Harbor Seals feed in the Bull Kelp forests along the shore as does the occasional Steller Sea Lion or River Otter.

Drive north 1.8 miles from San Juan County Park, turn right onto Mitchell Bay Road, and in another 1.3 miles go left onto West Valley Road. Travel north 1.5 miles to the visitor entrance on the left for English Camp, the other unit of San Juan Island National Historical Park. The parking lot has mixed maple/coniferous forest on one side and Red Alder stands on the other. In the conifer woodlands, look for Pileated Woodpecker, Chestnut-backed Chickadee, Brown Creeper, Pacific and Bewick’s Wrens, and Varied Thrush. The alder is productive for spring birds such as Rufous Hummingbird, Olive-sided and Pacific-slope Flycatchers, Hutton’s Vireo, and Swainson’s Thrush. Some of the oldest and largest known specimens of Bigleaf Maple grow near the barracks building. Check trees for a possible spring fallout of warblers—Orange-crowned, Yellow-rumped, and Townsend’s are the most common species. Walk down to the blockhouse and turn around to see the Osprey nest perched on a snag at the top of the hill. Swallows work the parade grounds and Rocky Mountain Junipers (another botanical curiosity for Western Washington).

Sheltered Garrison Bay is good for wintering waterbirds, Black-bellied Plovers, and Black Turnstones. The trails here are easy and are sometimes productive for forest birds. From the parking lot, hike up Young Hill. Douglas Maple—a dry-site species—thrives here and elsewhere on the islands, where it replaces the ubiquitous Vine Maple of the damper mainland. The view from the 650-foot hilltop offers the overall essence of the San Juans: grassy hills and oak forest, narrow channels and quiet bays, with the immensity of Vancouver Island in the distance.

Turn left from English Camp and continue north on West Valley Road for 1.3 miles to Roche Harbor Road. Turn left and continue 2.2 miles to Roche Harbor Resort (pronounced roach, like the bug), an old company town turned resort in the 1950s. Some of the purest limestone west of the Mississippi was quarried and burned in the kilns here to produce lime. The highly groomed grounds are not highly productive for birding, but the flower gardens are beautiful and a good place for hummingbirds. It is fun to walk the docks where you may see all sorts of boats, from old wooden classics to the latest in ostentatious pleasure vessels. The bay has all three cormorants, Bald Eagles, and Pigeon Guillemots.

Walk trails through the fairly young second-growth forest around the resort periphery to find flycatchers, vireos, thrushes, warblers, and the Cooper’s Hawks that chase them. Turning back, it is 10 miles to Friday Harbor via Roche Harbor Road (becomes Tucker Avenue in town), passing by more for- ests, fields, lakes, and wetlands. Finding a safe place to stop is difficult, but look for a possible flock of Trumpeter Swans in winter on Dream Lake at Lakedale Resort 5.1 miles from Roche Harbor. Keep an eye out for interesting species that might be found in these habitats on the way back to Friday Harbor.

LOPEZ ISLAND

Lopez is the third largest of the ferry-served islands, is fairly flat, and has amazing sites to view marine birds. Bring your scope for the best birding. From the ferry dock head south on Ferry Road 1.4 miles, turn right to Odlin County Park. Check the beach, overhanging trees, wetlands near the campground, and Upright Channel.

Return to Ferry Road and turn south; the road becomes Fisherman Bay Road in 0.9 mile. Drive 3.8 miles to Bayshore Road, turn west, and go 0.6 mile to Otis Perkins Park on Fisherman Spit. Fisherman Bay is a shallow, muddy bay full of ducks, shorebirds, and more from fall to spring. Scan west to San Juan Channel for marine and rocky shorebirds. Walk or drive 0.8 mile of spit to Peninsula Road, turn left, and continue 0.8 mile (right at Chestnut) to Fisherman Bay Spit Preserve. This jewel faces the entrance to Fisherman Bay and overlooks San Juan Channel. Walk the trails through the mixed forest, meadows and pond, then to the beach. Retrace your route to the ferry.

February 21, 2020

Jack

This is a great guide to birding in the San Juans. I live here and referenced it in hopes of finding wood duck areas. Additionally, I have seen surf scoters in Roche Harbor this winter (and it's actually pronounced "Roash" -trust me I work there, we always laugh when people mispronunce it as roach). Thank you for taking the time to put this together!

February 28, 2017

Randy Robinson

The ferry to San Juan Island is so expensive you might want to go with a group! Better yet is if you know somebody who lives on the island and has a car. It’s $13.25 to take the ferry as a passenger compared to $47.30 to drive your car onto the ferry.